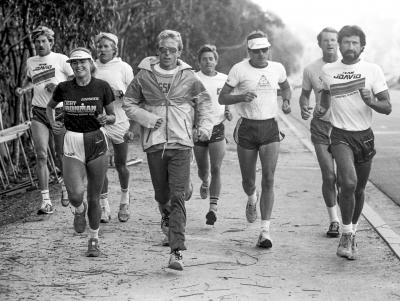

Left to right: Gary Peterson, Kathleen McCartney, ST, Tom Lux, Chris Miller, Ted Pulaski, Steve Fletcher, and Stan Silbert. Photo: Mike Plant

Like many things that shaped the sport of triathlon, the Tuesday Run was catalyzed mostly by accident. And a little design. Nothing but a group of like-minded endurance freaks in search of their mirror deviates…in search of speed. When that handful of San Diego-based triathletes decided sometime in the spring of 1983 to meet every Tuesday morning, it began a 20-year streak of pleasure and pain. The time was 7:30 AM. and the entry point was a public street adjacent to the private Lomas Santa Fe Country Club. The venue was 50-some miles of groomed trails.

Imagine that: 30 to 50 athletes--some wealthy, some almost homeless--all coming together for 30 to 50 reasons. The Tuesday Run was never conceived as a pure training ground or a preparation for the pro ranks. It began with just a few friends out for a trail run. As long (11-14 miles) and as hard (average pace 6:00 minute mile) as it was, the legendary run began like most group workouts: one person calls another who calls another and shazaam, here we go.

And when those callers included future hall of famers, Scott Molina and Mark Allen; and early elites, Kenny Souza, Gary Peterson, George Hoover, Paul Huddle, and Wally and Wayne Buckingham…you just knew it was going to get snappy.

During the early 1980s, coastal North San Diego was not the best place to be a budding elite triathlon: it was the only place. Boulder was still a sleepy backwater of neo-hippies and counter-culture rock climbers. Australia was barely awake to the multisport movement and European endurance athletes couldn’t find a way to separate themselves from pro cycling’s bourgeoisie. But in places like Del Mar, Encinitas, and Solana Beach—the foundational locales of professional triathlon—there existed a dozen or so athletes who thought that maybe, just maybe, this new sport could offer a few bucks to pay the rent. A way of supporting the multisport dream. And on any given Tuesday morning, you’d find the best triathletes in the world tramping around those trails at speed.

Mark Allen and Kenny Souza, two speedsters talking strategy

Paul Huddle, who had moved to San Diego to train in 1982 after graduating University of Arizona, reflected on those times. “I remember rolling into the parking lot and seeing Steve Scott, Kevin McCarey, Mark Allen, Scott Tinley, and Kenny Souza casually talking and instantly feeling an overwhelming urge to throw up.”

It’s hard not to feel wistful about those runs. Photo: Mike Plant

In 1841, Pio Pico, then Governor of Alta California’s Pueblo of San Diego, offered the 8,824 acres of Rancho San Dieguito to a group of local Mexican settlers who farmed the land just inland from where San Diego’s Solana Beach now exists. By 1906 the Santa Fe Railway had purchased the entire land grant with the idea of planting blue gum eucalyptus trees for use as railroad ties. But the wood wasn’t dense enough to support the larger, heavier trains, and in the early 1920s the area was reconstituted under a community development plan; a low density, semi-rural township intended to mirror a Spanish Colonial Revival. The eucalyptus trees remained and thrived, but the renamed Rancho Santa Fe (RSF) was considered hinterland, nearly 20 miles and half a day’s ride from San Diego’s downtown. Property values were relatively low. Teachers and farmers and small business owners bought on the ranch.

Between the late 1920s and late 1960s, “Rancho” was primarily occupied by isolationists, artists, and those with the equine tendency. Horseback riding, both Western and English, were considered outstanding on the ranch. In 1926, film stars, Douglass Fairbanks and his wife, Mary Pickford, both horsey-folk, purchased a large parcel with a year round stream they damned to form an idyllic pond. Word of the perfect climate and rolling coastal geography spread slowly. But it spread.

In 1936 crooner, Bing Crosby, acquired a separate ranchette and along with his Hollywood pals, Pat O’Brien and Gary Cooper, helped open the nearby Del Mar Racetrack as a place to race their ponies. They also built a golf course on the ranch and formed a rather exclusive club of their mostly out-of-town glitterati. But for those Tuesday runners who would come 50 years later, it was the world class network of trails that mattered.

At the root of a Tuesday Run family tree you’ll find Scott Molina

When Scott Molina moved to San Diego in the fall of 1982, he went in search of off road running. Raised in the untrammeled veldt of San Francisco’s East Bay, Molina sought the proximity of open space among SoCal’s growing coastal density.

“When I first moved to Del Mar at the end of ’82, I used to swim at Loma Santa Fe Country Club so I ended up running out there on those Rancho trails a lot. I remember thinking that I had found the best place in the USA to run.”

And through his connections with Team JDavid, Molina met and befriended local tennis pro, Gary Peterson. Peterson’s family had lived near Rancho Santa Fe for nearly 50 years and as a kid he had explored every inch of those famously- confusing 50 miles of trials on bike, foot, horse, and late at night, off-road motorcycles. No one knew the trails like Peterson.

“Gary,” I asked him sometime in 1983, “how long did it take you learn these trails?”

“I don’t know, maybe 10 years. After our high school cross country coach started bringing us out here to run and we ended up running a lost 20 miles instead of two, I decided to learn them well.”

Molina and I would meet Peterson on Sunday mornings for a causal distance run and soon realized that we needed to carry all our own water, food, clothing, and a compass. It could be one hour or four. That was the way Gary taught us the trails. That was the way we rolled in 1983. But the trails, that magically-carpeted network, were arguably the best any of us had seen. Less than three miles as the crow flew from our homes near the beach, the air was clean, the views were long, and life on the ranch trails was good.

Peterson, a highly-likable and largely-forgotten figure in the history of triathlon, remained as the head tennis pro at Rancho Santa Fe Country Club for a few more years until, dead tired from a 90-mile bike ride with Molina, he sat down while offering a lesson and fell asleep. When he woke up his student was gone. And so was his job.

Over the years I have tried to gain access from various RSF organizations to the trail map that mythically exists. But as Rancho Santa Fe was become increasingly wealthy and elite, knowledge of the traills remains now as it was then: to those willing to explore and avoid the occasional security patrol bent on limiting use.

Tuesday Run circa 1987 (left to right). Paul Huddle, Drew Renick (sp?), Tim Sheeper, Wally Buckingham, Dave Jewell, Wayne Buckingham, Bob Decker, Craig Leher, Carter Goodnough, Barry Oliver, ST, Tony Richardson, Joel Thompson, and Mark Montgomery.

When the Tuesday Run unofficially began, it was never official. There might have been anywhere from 30 to 50 runners with abilities ranging from casual jogger to Olympic contender. And no one ever took charge. Not officially. No announcement in the paper, no entry form, no insurance, no coach, and until the Europeans showed up in the late 80s, very few pretensions. We’d all start out at a very slow jog, allowing the late arrivals to catch up after they’d stashed their keys or chugged that last sip of gas station coffee. We moved wistfully down through the marked paths of the adjacent San Dieguito Park and onto Sun Valley Road as some collective, happy to be fit, free, and unencumbered on a Tuesday morning.

For the first mile, you could look around and see your best friends, smiling, joking, young, tan, and bitchin'. Tuesday was long enough after a past-weekend race to forget the vagaries of failure and too soon to be thinking about the next Saturday or Sunday’s looming event. Tuesday morning was a time for the present. By mile two, small groups would begin to form; whispers and grunts and suggestions: How do you feel, Bro? Where’s Bob and Mary? Who’s the new guy in neon? Do you have a loop in mind?

Organically sorted, by mile three, gloves came off.

“Don’t let the simple title fool you,” Huddle muses on the Tuesday Run. “Yes, this was a group running ‘workout’ but this was also an event. No one who went to a Tuesday Run slept well on a Monday night. They knew that the following morning would bring 11 to 14 miles of pain and suffering on a scale that often exceeded weekend races.”

The quickened pace began innocently enough. Someone stopped laughing at the jokes. They’d adjust their headband, move to the front, clear their chest and spit. Nothing was said or needed to be. When the Tuesday Run started its thing, it felt as a supercar shifted from second to fourth gear. The lead pack dropped runners off the back like stages from a rocket. And by mile four the groups were set. But the route never was. And that made it interesting. Almost mythic.

Between 1983 and perhaps 1988, we ran a different loop every Tuesday with different intensities at different points. Chosen by some non-descript historical hierarchy, we’d assemble our path based on a variety of egalitarian factors.

Mark Allen wanted to go shorter and harder.

George Hoover wanted to run by a girlfriend’s house.

Greg Welch wanted to find a few golf balls near the driving range

Tony Richardson was hungover. Kathleen McCartney had new trail running shoes. Murphy Reinschreiber had a meeting at nine. Wally Buckingham was afraid of snakes.

But mostly the route was chosen by those who knew the trails. And had earned their place up front.

Ron Smith could run 7:45 minute miles like a metronome; the steady tic tic as solid as his soul. He’d owned a house in RSF for a period but gave it to the EX. Photo: Mike Plant

“You never knew exactly what to expect,” recalls six-time Kona champion, Mark Allen, “or from whom the dynamite trigger was going to be pushed.” The group never ran less than an hour and rarely more than two. But in that malleable window of time you could cover a lot of beautiful ground that, if you weren’t suffering interminably from the pace, was in fact, quite beautiful.

In some ways, the Tuesday Run was the first real aesthetic approach to triathlon: you showed up with a kind of wild-eyed wonder in your heart, let it all hang out amongst those blue gum trees, and went home thinking how wonderful that suffering had been. If you made it home.

“I was the victim of the ‘letting visitors lead’ trick,” remembers Heather Fuhr. “The first time at the Tuesday Run, Roch (Frey) and I were excited to be running with the big dogs, only to get dropped and completely lost. Two and a half to three hours later we finally made it back to the car. Lesson learned from that day on, know where you are going and don’t trust the big dogs.”

If you didn’t know the trails and were uh…abandoned, there were only two choices, both of which were bad. You could keep running in circles for hours or days until you stumbled on the parking lot or you could ask for directions from a local resident who would regard you as an interloper that might diminish their property values with your sweaty, shirtless presence.

On one occasion, some hot-shit high school kid from Kansas on spring break showed up and asked who he might shadow if he wanted to prove himself. I pointed to the old silverback, Ron Smith, and told the kid unless he knew the trails and was willing to do everything the lead back offered, Mr. Smith would be his best bet to get home before dark.

Appropriately rebuffed, the kid from Kansas asked about the skinny guys with the tan. “Them?” I nodded to a group that included three world championships and an Olympic medal. “They’ll leave you for the coyotes without losing sleep.”

The best tactics were the least compatible with burgeoning egos: sit back as long as possible, hold your powder, shut your mouth, and let your legs tell your story. No one really wanted to leave some unsuspecting kid five miles from home. But if he showed up with glory in his eyes and a begging chip on his shoulder, I for one would knock that thing into the next county.

Here’s a dime, pal. Call all your friends for a ride home. See you next week.

I’m not sure the Tuesday Originals were considered menacing. But in some way, I hope the mythology sticks. The notion of hierarchy, apprenticeship, and tenure has been lost to many echo-boomers and gen-xers. If we were less-than-gracious to some kid who felt s/he was owed something for their natural talent, so be it. I hope they paid the lesson forward.

By 2012 there were roughly 3200 people living in Ranch Santa Fe, and according the US Census, they were 94% white and largely Republican. In the 2008 presidential election, RSF locals voted 66.4% for John McCain over Barack Obama. Countywide, the tide for McCain was just 43.7%. The previous two years, 2006 and 2007, Forbes Magazine had noted RSF as the second most expensive zip code in the United States and by 2011, the median price for a home was well over $2.5m. Cleary the Ranch had become a very desirable and conservative place to live.

The 50-plus miles of horse trails were regularly groomed with a puree of blue gum eucalyptus leaves to reduce erosion and keep that pesky clay-dirt from clogging hooves and heels. The gentrification was in full bloom and Tuesday runners, on occasion, felt the wrath of wealth and privatization.

In an effort to retain access to the trails, we began a campaign of disinformation. Instead of a loosely knit collection of rag-tag triathletes, we began telling anyone we encountered that our Tuesday morning running group was “training to represent the great country of America in the Olympic Marathon.” We began wearing anything red, white, and blue and would break into a round of God Bless America if accosted on the trails by local right wing doubters. It worked famously for a while. But in an effort to find long flat sections to run snappy four to six minute efforts, we kept migrating to the golf courses. And the mixture of ideology and intent rarely went well.

For a period, Tuesday was Ladies’ Day on one of the courses and I can remember watching several women purposely take aim at the runners from the tee while other senior cougars gawked at the shirtless hunks of Tony Richardson and Rob “Beef” Mackle. On more than one occasion we were met by private security and Sheriffs at the golf course gate.

Looks like were headed back to the hills, Boys. Follow me, I know a shortcut.

As mellow as the parking lot seemed, gloves would come off.

Rancho Santa Fe has always had this anomalous relationship with athletes and sports. Many professional athletes have chosen RSF as their home, among them MLB greats, Trevor Hoffman, Steve Finley, Jack McDowell, and David Wells, Serbian tennis pro, Jelena Jankovic, NBA stars, Steven Kerr and Luke Walton, professional golfers, Phil Mickelson and I.K. Kim, and Olympic snowboarder, Shaun White. A host of others, full or part time residents, would remain anonymous and folded into the rural quietude of the ranch.

Mark Allen lived for a period on the ranch as a guest of Team JDavid matriarch, Nancy Hoover. British athletes, Glen Cook and Sarah Coope were also part-time residents, enjoying the quick access to some of the best triathlon training anywhere.

Jurgen came to America as a driven Teutonic and left as a fun-loving SoCal-conversion

The first European triathlete to show up at the Tuesday Run was Dutchman, Rob Barel. Quiet and respectful, Barel was a welcomed flavor to our band of amero-centric athletes. Many of the runners had not competed in Europe and welcomed his dry wit and poker-faced replies to our questions about training and racing Over There. Cook and Coope followed shortly and fit right in with the established group.

But as the commercial opportunities within the sport grew, more European athletes began training in North San Diego County. And they inevitably showed up at the Tuesday Run with their tall socks and taciturn attitudes. These were good athletes from France and Spain and Germany and the language within the group turned multicultural. Until that fateful day when it turned ugly.

One of the German athletes was complaining that the pace had been too slow for his training schedule. He’d wanted to go less distance but at a quicker pace. I think it was San Diego native, Tony Richardson (who could be as direct as a nail gun to the temple) that told the athlete if he didn’t want to run with us then he should simply go back to the Fourth Reich, or something to that effect. The German athlete reminded Tony that if he ever chose to train in Germany, he would show him equal (dis)respect. Tony spread out his hands as if to say, “Look at all this around you” and replied that he had no reason ever to leave his paradise, let alone try to find decent trail running in the Fatherland.

The very next Tuesday, the German contingency, now led by the likable but cocky neo-pro, Jurgen Zach, showed up on the Tuesday Run. Interestingly, they pre-opted for a fixed and permanent route; something with less confusion and decision. This created huge conflict within the running group: at mile two, you had to make a concerted choice between following the eclectic whims of old-school trail bosses or the regularity of this new, Germanic-catalyzed, one pre-identified loopers.

The end result was that the now-standardized route increased awareness from local RSF residents, particularly the golfers. But for those wanting a taste of the now-famous Tuesday Run, they could compare their times from week to week. They could get wasted and find their way home. By the late 1980s the measurement of multisport had begun to flow and there was no way to turn it off.

“Jurgen Zack turned what used to be a true fartlek run into an 11-mile race,” remembers Paul Huddle, in jest. “Clearly we’d been doing it all wrong. We hadn’t been comparing our times from one week to the next and this meant we didn’t realize that you could make up A LOT of time. What used to be a conversational warm-up was eliminated (3-minutes saved). We stopped any slower ‘recovery’ periods that, in the past would let everyone regroup and tell a joke before starting the next effort (4-minutes saved).”

Over the years, that band of eclectic and original trail bosses shrunk from 13 to three, and then just before the run fell victim to loss of interest and originals, there was no one who wanted to sample the fruits of the best running in the USA. It was heart rate and time over fixed distance that mattered.

In the roughly 15 good years that the Tuesday Run was held in RSF, some very strange things unfolded. Countless runners had been lost to the network of trails that appeared out from someone’s backyard fence and then disappeared into the fold of some tall shrub or stand of trees. To lead the Tuesday Run, you needed that knowledge of the trails, great running skills, and five years of regular attendance. It helped if you’d won at Kona.

Rock salt bullets had been spewed from a shotgun as the group crossed private property beyond the ranch and the smell of ether waifed; that indisputable potpourri of chemicals cooking. Genitalia and breasts had been exposed, egos built and destroyed and small, momentary legends made and lost. When Deon Laurens showed up, fresh off the boat from South Africa, he donned a matching bikini bottom and bra top. That’s what he was used to. No big thing. No pun intended.

Duathlon superstar, Kenny Souza, would often drive down from his parent’s home near Los Angeles just to test the waters. A few years later, on Tuesday, March 25th, 1997, Souza claimed he had “run by this big house just off the trail on the way to the workout and there were a lot of weird dudes in purple Nikes.” We all laughed. But the next day, it was discovered that 39 people had committed mass suicide in that trailside house as part of the Heaven’s Gate cult. They all wore purple Nikes in their effort to catch a ride on the Hale Bopp comet.

Or you may have heard the oft-told story of the Euro-star-to-be who demanded a 47-minute run at a pace to his liking. But when the Tuesday Run regulars, a long way from their cars, looked at their Timex watches and were faced with said Euro-star’s in-your-face query about his place in the pecking order and his place in the temporal-dynamics of that Tuesday Run, all Tony Richardson could say was, “47 minutes out, 47 minutes back.”

Gloves came off.

Besides knowledge of the land, respect could be earned if you a) didn’t try and lead before your time, b) kept up with the lead pack every week, and c) ran a fast mile for time. Once we had mostly acquiesced to the fixed loop, we found a relatively flat one mile section of hard dirt and pavement that began near mile 11 of the 13-mile loop. The timed mile began in front of the plywood cow on El Secreto Street and ended at the trailhead just after the bend in the road on El Camino. It might’ve been a tad short but if you weren’t running under five minutes then you weren’t in contention. Everybody knew who the sprinters were so the strategy was to drop them early. Just boys being boys with some thought of a psychological advantage come race day. Every pack had their own timed-mile heroes; athletes breaking the eight, seven, and six minute barrier and limping back to their cars with global grins.

“Set a PR on the Tuesday Run,” they’d write their training logs, “and then shared a sweaty water bottle with Paula Newby Fraser.

On occasion, pure runners would show up; the likes of Steve Scott, Tom Lux, Jay Larson, and Kevin McCary, and someone with a foreign name from a foreign country and they were all very fast.

“I remember feeling like those sessions were getting a very real reputation,” remembers Scott Molina, “when Steve Scott showed up. I nearly shit myself (which I did pretty often anyway). I think we did a flat mile near the end of that run in about 4:36. Running with those dudes gave me a tremendous amount of confidence.”

And there it was, or there the Run went. Photo: Mike Plant

“I have fond memories of that run,” muses ITU Triathlon World Champion, Greg Welch. “Twelve or 13 miles as a weekly workout, maybe a race. But my favorite part was that flat mile across the back of the golf course. We dodged stray golf balls and were yelled at by lady golfers.”

But, Greg, the very best part was…?

“There were so many athletes from so many different places and backgrounds.”

And what about Paul Huddle?

“He was one of the originals,” remembers Souza, jumping in. “Huddle was okay on the flats, below average on the up hills but could run downhill like a frickin’ bowling ball.”

A bowling ball, Kenny?

“Yeah, something big and fast and round and scary. Just like Paul.”

When asked about his memories of the Run, USAT Class of 2014 Hall of Famer, Dan Emfield, remembered more about who could eat the most pancakes at the Hideaway Café after the run and who was using the run as a kind of dating service. “I remember Murphy Reinschreiber hanging back with Shannon Delaney. Now that was a shrewd move.” These details, some would argue, matter as much as other legendary performances.

“I don’t remember much from the 300-some races I ever did but I remember quite a few moments from the Tuesday Run,” recalls Huddle. “The Tuesday Run was the single most important workout, social club, rite of passage, and event in the early days of triathlon.”

It’s hard to say why the Tuesday Run ceased to be a viable event. The residents of Rancho Santa Fe were increasingly protective of their trails and began asking for proof of residency while we were screaming down some desolate piece of dirt at a 5:30 mile pace.

“Excuse me, Sir, but do you live here? You know these trails are reserved for RSF residents.”

“Huh?” we’d offer in a passing blur. “Take it up with the Olympic Training Committee.”

Some of the originals faded from glory, some moved away, some died, a few retired; faded stars in a passing limelight of the growing, white-hot spot of this new Olympic sport.

“We all knew that is was the group’s collective, inflated ego that helped us all to elevate ourselves to impossible levels…together,” recalls Mark Allen. “And that no one could have done it alone. And for that we were all thankful for the Tuesday Run.”

Left to right: Richard Brown (UK), looks like Christian Bustos (obscured) but I think this may have been too early for him to have been there…maybe not, Janet Hatfield, someone in background between Hatfield & Cook, Glen Cook (UK), Billy Duvel, Tim Sheeper (in background next to Billy Duvel), Rob Mackle (crouching in foreground), Tony Richardson, Dave Jewell (in background next to Sheeper – between Tony & Wally), Wally Buckingham, someone behind Wally, Mitsuhiro Yamamoto, Wayne Buckingham (crouching), some poor Japanese guy, Paul Huddle in a sweet visor and the Bee Power 10-mile Run t-shirt – an AZ running race that he ran in High School…and wore that t-shirt to school along with his running buddies because he was certain it would get chicks, and Jim Curl – crouching (caption courtesy of Paul Huddle)