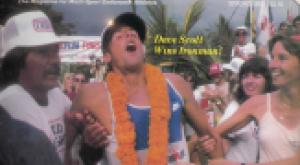

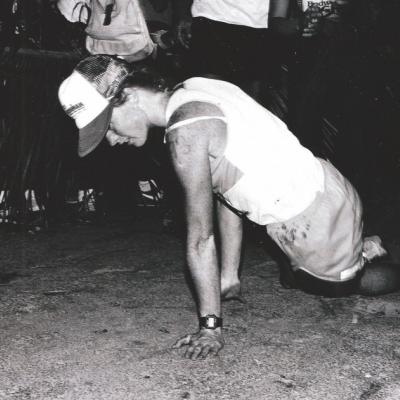

Julie Moss made history the hard way. The impact on the sport of her dramatic finish was felt around the world and for many years to come.

The short and thick man in the bar keeps looking over his shoulder toward the door. He wears a tweed jacket with pressed slacks, matching, and appears to be having an intimate relationship with his cigar. The short and thick man appears to stand a bit taller than the other Kiwis who are actually bigger in this small town bar on the shores of New Zealand’s Lake Wanaka. He seems confident in a New York style. Nobody messes with him and his cigar. And I am intrigued.

“You look out of place, Sir.” I offer. “Not from around these parts?”

“Neither are you, Hot Shot.” He fires back. “And I know that because I’m the reason you’re here.”

Barry Frank, then President of Trans World International, the television arm of IMG (International Management Group), the largest sport management firm in the world, has called me out. He extends his hand and offers to buy me a beer. We are both in New Zealand for the late February 1982 version of Survival of the Fittest, an early Reality TV/trash sports thing. Frank is the Creator/Producer and I am simple talent; one of the 12 male competitors. He had invited me by phone from Manhattan. But he sounded taller on the phone.

“Glad you could make it, Scott. I enjoyed watching you win in Kona a few weeks ago.” Frank is still looking at the front door.

“Uh, thanks for the invite here, Mr. Frank. And thanks for the beer. But are you expecting someone else?

“Julie.” He pulls a long drag on his cigar and I cough. “Julie Moss is the new star.” And I know then that the ripples of the 1982 Ironman and Moss’ Big Crawl, not three weeks prior, would lap at the shores of triathlon for decades after the scrapes on her knees healed.

# # # #

The backstory of Mrs. Moss’ crawl to grace and Mrs. Kathleen McCartney’s unlikely world title is the story of how triathlon ever made it past its cult-sports infancy. The accidentalness of it all both astounds and amazes. Julie Moss was not a great athlete. But neither were 95% of both the men’s and women’s field in the 1982 Hawaiian Ironman World Triathlon. 580 competitors started that February 6. It was mostly a challenge, fer chrissakes. No prize money. No fame. Bragging rights and a TV sports cameo. The 1982 Ironman was an excuse to go to Hawaii when the average temperature in Chicago was 19*. Moss was a PE major from a state college in California. McCartney was a waitress at a beachside bar and grill. Two young women caught up in the wave of early triathlon mania, chasing boyfriends and college degrees. But then the magic happened.

And the world sees it unfold on a box in their living room, backlit and scored to a Tim Weisberg flute playing Dion Blue.

# # # #

Two years earlier, Robert Iger, (current President of Walt Disney Corp) then working for ABC Sports, had identified the Ironman Triathlon on Oahu as an event that Wide World of Sports should cover. He’d read the McDermott piece in Sports Illustrated and was smitten with the drama. ABC had successfully produced the coverage in 1980 and 1981 and after solid viewer feedback, had high hopes for the 1982 show. But they had no idea what they would get with Moss/McCartney. And it almost didn’t happen.

Ironman was owned in majority by one Valerie Silk at the time and Silk, admittedly underprepared for the commercial success of the event, struggled with the newfound interest of Corporate America. ABC was offering little to no compensation for the rights to broadcast at the time.But the TV publicity was a boon even Silk well understood.The race she had inherited in a divorce settlement from her ex -husband, Hank Grundman and his two Nautilus Fitness franchises, was now a legitimate sport because it was on national TV.Now what?

Enter Rodney Jacobs and his renegade film production company, Free Wheelin’ Films. Jacobs, a SoCal surfer transplanted to Aspen, CO on the backs of a college-alternative gig showing Dick Barrymore ski films in high school gyms, had seen the rise of triathlon and knew that Ironman was an undersold gem. Armed with an Anheuser Busch relationship (Jacobs had produced several of the first Clydesdale horse/beer commercials), he showed up at Silk’s one bedroom apartment outside Honolulu with one offer that had many parts.Jacobs would broker the first title sponsor for the event in return for access to film the event. All Rodney wanted were the rights to submit his style of indie production to this emerging sport. Just give me a chance to set up a few cameras, Silk might’ve interpreted his request, and chat with a few athletes and I’ll get you a few thousand from Bud Lite. Jacobs’ intent was to produce a 28 minute documentary on the event “for use by schools, libraries, and book clubs” he remembers.The fact that the Anheuser Busch (AB) funding meant that he and his crew would spend several weeks in Hawaii during the prime winter swell period was just another accidental caveat.

“I posed AB send me and Tom Warren (winner of the 1979 Ironman) to Honolulu,” Jacobs remembers, “to try and tie up name and title sponsorship rights on the heels of the Sports Illustrated article (link to article). They thought I was out of my mind. Never heard of the event! I gave my word that they would be well served.”

So, Jacobs sat in Silk’s apartment, typed up the sponsor agreement on her word processor and handed it back. She signed. And when the February event rolled around, Jacobs and his film crew, including host and narrator, Bruce Dern, appeared better prepared than ABC to cover the 1982 Budweiser Light Ironman Triathlon. Free Wheelin’ Films had already done hometown, pre-race athlete interviews, scouted locations, shot background scenery, rented vans, and hired locals-only security. And when ABC got wind of what commentator, Jim Lampley would later call in his on-air voice over, “that ubiquitous film crew,” they were furious. Tensions ensued, jockeying for camera position became its own side show, and as Julie Moss had her noble moment in sports history, ABC Producer Bryce Weisman stood in a trailer near the finish line berating Valerie Silk for allowing Jacobs’ crew on the course.

Why should he be mad? According to Jacobs, who negotiated that singular contract giving AB/Bud Light title sponsorship in 1982 for $2500 along with his company’s exclusive rights to film, everybody would later benefit.Never mind that ABC, according to Jacobs, also thought they had exclusivity to film as indicated in a contract executed six months after his. Anheuser Busch would buy commercials onto the Wide World of Sports show and market their sponsorship of the event, and ABC would position itself as the leader in developing new endurance sport markets. Never mind that Valerie Silk might’ve accidentally offered conflicting “exclusive” contracts to film the event. History is rarely fair. Val was acting on behalf of the competitors, her Iron-children. There is no fault in her altruism.

# # # #

A few hours before Moss’ Big Crawl, I had won the event and now sat on a curb near the finish line next to 1979 winner and my San Diego neighbor, Tom “Tug” Warren. We were sampling the new “light beer” and Warren was not pleased. As a successful bar owner, he was a student of suds and refused to drink the carbonated water with a hint of hops. Suddenly there was a commotion around the finish line and we stumbled to our feet in the early dark.There were lots of people crowded around a girl who appeared to be moving toward the finish line as if summiting Everest of tossing grenades into enemy foxholes. The sun had set and the scene became eerie under the white hot cameras and people screaming.

“Please! Somebody do something.”

“Don’t touch her. She’ll be disqualified.”

“I can’t stand it. Please, help her up.”

And then there was a long silence.

The ABC footage shows another young woman slide by in a crisp white tank, her hair pulled neatly into a long ponytail. Kathleen McCartney crosses the finish line before Moss and ambiguously , has to be told by a volunteer that she is now the fittest female endurance athlete in the world.

And Julie rolls onto her back, offers this “did you just see that?” smile, and extends her right arm across the line in a kind of backstroke salute. She is done. But her new life is just beginning.

Warren and I looked at each other and shook our heads. He might’ve said something and he might’ve not. “Gnarly.” Or “well, that was heavy.” Perhaps he mumbled about the girl on the ground forgetting to eat enough food. I would’ve agreed. A Coke and Snickers away from glory.

“It’s been a long day,” somebody else said. “And we’ve just seen amazing.”

Warren shrugs. Yep. Pretty cool.Shoulda had that Snickers.

Not 30 yards away, a young ABC assistant to an assistant bursts into the trailer where Weisman fumed and said something like, “Sir, you need to get out here. Something special is going on.” A fly on the wall wants to see facial expressions. And not 48 hours later, back in New York ABC pushed aside other sports shows to get the Ironman on TV during a coveted Saturday afternoon slot in February.

The Image Masters sense greatness and ratings. Moss and McCartney are flown to the City to do interviews and shop and be celebrated for what Wide World of Sports anchor, Jim McKay called “perhaps the most dramatic moment in the history of Wide World.” Moss and McCartney are meeting with agents and working the talk show circuit. But as it were, ABC Sports might not have had all the goods. Under the pressure of a camera angle fight with Free Wheelin, ABC ended up with perhaps only one long wide angle view of Moss crawling while Jacobs had secured several angles. He recalls:

“I was directing all the camera crews via radios and was with (Co-Director) Peter Sellers at the finish line preparing for the master shot. So I dispatched another cameraman back up the course to follow Moss/McCartney with specific instruction to ‘get in front of anybody with a camera and right next to the girls no matter what and I will cover for you’. Then it all unfolded and we ended up having the action covered with not one but three camera angles.

While the ABC coverage went on to televisual sports fame, the Jacobs documentary remains a cult classic on YouTube. Jacobs, for his part, became a favored son with Anheuser Busch for pushing them into a title sponsorship with Ironman that lasted nearly a dozen years and helped to launch the light beer phenomenon.

# # # #

And then Moss and I ended up in New Zealand a few weeks later. That’s when Barry Frank, the early king of trash sports, made it known that triathlon was undersold and he was going to blow Ironman out of the water.

“Scott,” he leaned into me in a corner booth at the Lake Wanaka bar, “Ironman is great and all that but they don’t know TV sports. I do. I’m sending you to Monte Carlo in a few weeks and I want you to consult on the most spectacular triathlon ever staged.”

“And Julie?” I asked.

Barry looked at me and winked. He might’ve said something about how Julie’s place in sports history was only beginning. But I already knew.

I don’t recall watching the 1982 Ironman on TV that year. I hardly ever did. But someone had taped in on a new machine called a Beta Recorder and stopped by to show it to me after I came home from work one night.Anheuser Busch had started sending me five cases of Budweiser Light every week by then, and while I appreciated the new sponsorship, I simply couldn’t give it away fast enough. But we opened a few and watched Julie crawl and Kathleen win as the grainy footage unfolded with the haunting Tim Weisberg flute in the background.

“Your recording is interesting,” I offered, “but it’s awfully dark.”

“That’s the way it was on the ABC broadcast,” my triathlonfriend offered and proceeded to tell me that he’d heard that the ABC film crew hadn’t secured good footage of the Moss/McCartney finish and might’ve gotten it from some local Kona guy who happen to have his new camcorder.Urban legend, I thought, but decades later when I asked Ironman Hall of Famer and fabled producer of many Ironman television shows, Peter Henning, about the legend, he could neither confirm nor deny.

The act of connecting place with significant events is a kind of life’s pugmark. Depending on age, we might remember where we were when a) President Kennedy was shot, b) the Challenger exploded, or c) the events of 9/11/01 unfolded. But one could never equate one young women’s failure to stay fueled with events of international consequence. Still, when the powers of media and belief meet on the fair fields of play, lives can and will be changed. Many are the stories of how The Big Crawl altered undetermined courses. Years later you may meet a person in an elevator and you end up talking sports. And by the time you exit at floor 53, you have learned that he or she was deeply moved by the image of Moss crawling.

Armen Keteyian, Lead Correspondent for 60 Minutes Sports, wrote a searing piece on the event for the San Diego Union Tribune that changed his life.“In my mind’s eye,” He recalls, “I can still see Julie and I sitting on that beach in Carlsbad telling her story, drawing lines in the sand. And I can still see myself sitting in a nearly empty newsroom one Sunday afternoon at the Union writing in an emotional rush.”

But what might’ve been lost in the mythologizing of Moss is the athleticism and tenacity of Kathleen McCartney. For her part, she was more than a very good athlete. “There is no doubt that Kathleen was better prepared for the event,” remembers Julie Moss, “and she proved it by continuing to win at shorter events over the summer of 1982.” Still, McCartney or Moss might’ve gone on to win dozens of races in their collective careers and that extended excellence would pale in comparison to the singular day in February 1982.

History will not judge McCartney or Moss for their athletic success well beyond that day they accidentally dueled under a topical sun. Both are fine with their accomplishments and in some pushback against history’s misanthropy, are in better shape now in their middle, divorced 50s, after kids and sun and stress. They might wonder of the three decade effects of theirfifteen minutes of fame.

Kathleen might wonder about the effects of that rock first dropped in the pond; about why she was contacted by a La Jolla-based financial services company called JDavid in the spring of 1982 to be the first well-sponsored athlete in the sport. Perhaps $800 or $1000 each month to be the Golden Girl. Team JDavid would become the first and most powerful triathlon team in the sport’s early history. They would enable a stable of top athletes to experience the reality of professional sport with all its glam and guts. But JDavid the company (Jerry David Dominelli and partner, Nancy Hoover, amongst many) turned out to be nothing more than a grotesque Ponzi scheme that bilked well over $100 million from investors, many who could never afford to recover—triathlon’s own Madoff.And McCartney had loved the principals as family. The vagaries of elite sports had come hard and early on the heels of the aesthetic innocence of the 1982 Ironman.

# # # #

Barry Frank’s Tri-Country Triathlon was never held. We had designed a course where athletes would swim from a boat into Monte Carlo, ride their bikes to Italy, run through the edges of France and end up back in Monte Carlo. But on September 14, 1982 Princess Grace Kelly, the expiated American actress, died in a car accident on the Corniche and all of Monte Carlo mourned. Sporting events were cancelled for many months and the Tri-Country Triathlon was moved up the road to Nice where it became the first major triathlon in Europe. Julie and Kathleen were there for that cold November event. Neither won the event. But Julie’s future/former husband, Mark Allen did. It was the first of his ten victories at Nice.

In the late 1980s, Valerie Silk sold the Ironman to an opthamaligist from Florida. He later sold it to a large venture capital group which currently manages the brand and its properties.Title sponsorships for the World Ironman Championships in Kona, Hawaii cost many zeroes. Julie Moss and Kathleen McCartney finished the 2013 Ironman World Championships in fine shape. They now give motivational speeches to groups, parrying each other’s old and new feelings about the effects of that ancient February. Moss, when queried about her contributions, has achieved a level of maturity born of a thousand questions. “Back then I never was comfortable with what my actions brought to the race. But now I understand and accept my contributions.”

World Triathlon Corporation, the entity entrusted to sustain what fortune and commercial fate the Moss/McCartney Show fueled, offers in their official rules that, “No form of locomotion other than running, walking or crawling is allowed.”